Digital banks are on the rise Down Under. However, competing with the big four banks won’t be a walk in the park.

Australia’s banking sector is changing in a big way. Up until recently, the big four – Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Westpac Banking Corporation, Australia and New Zealand Banking Group and National Australia Bank – have basically reigned supreme. However, a new wave of digital banks has swept in across Oz in the last year, challenging the incumbents for a slice of the market.

Up was arguably the first Australian neobank to enter the market when it launched in October 2018. “The story of how Up started actually goes back about five or more years,” Dominic Pym, co-founder of Up, tells FinTech Global.

Back then, he and his co-founder Grant Thomas ran a software company called Ferocia together. It specialized in creating software for banks, which eventually led them to design digital banking solutions for big banks.

However, a few years ago they found themselves spending first two and half years working with one major bank and then 18 more months with another big one only for both projects to be scrapped before launch. “By this stage we’d spent around four years building digital banks and we’d certainly developed a deep understanding of the banking sector, but we never got to see our software in market,” Pym says. “As you can imagine we were deeply frustrated – but also resolutely inspired to launch a truly digital bank here in Australia. And so we did.”

They began to develop Up in September 2017. As they worked on the solution, things were changing in Australia. And for some, this was about time. “Challenger banks have been rising in countries like the UK for the last ten years, but the licensing requirements that were in place for a new bank to start in Australia has meant very little disruption had happened,” Elizabeth Barry, FinTech editor at Finder Australia, the comparison site, tells FinTech Global.

Over the past ten years, Britain has birthed challenger banks like Aldermore, Monzo, Atom bank, Monese, Revolut and Starling Bank. Similarly, Simple and GoBank has launched in the US and Europe has seen a smattering of neobanks like Dutch bunq and German N26 – reportedly gearing up for an IPO – open in the same time.

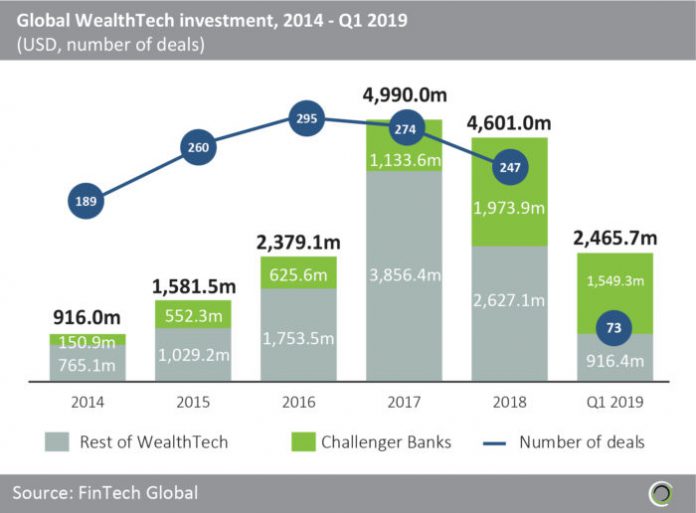

Globally, challenger banks have drawn in a lot of investment, according to FinTech Global’s own research. Investment in the sector has jumped from $150.9m in 2014 to $1.97bn in 2018. And it looks like its growing, with the first quarter of 2019 alone seeing $1.54bn invested in challenger banks globally.

Keeping this background in mind, it is understandable why some thought Australia was falling behind other countries. “However, this all changed in May 2018 when a new licensing regime lowered the entry requirements for a new bank to start,” explains Barry.

The new restricted authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) licence granted by Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) enabled new organizations, like neobanks, to enter the market and conduct a limited range of activities for two years.

All these things happened as Pym and Thomas were developing Up. However, they didn’t go for the restricted ADI. Instead they leveraged a partnership with Adelaide Bank and Bendigo Bank for two reasons. “Firstly, we wanted to be first to market,” Pym explains. “We also wanted the freedom to do things the way we wanted, but with the established trust that comes with the backing of Australia’s fifth largest bank.” And in October 2018 they officially launched Up.

They were soon followed by others. The past few months have seen the startup 86 400 gear up to take on the big four by acquiring an Australian banking licence and by tapping Morgan Stanley for a $100m funding round. Similarly, Judo Bank has raised a $270.62m round and Xinja closed a AUS$2.6m crowdfunding round in January.

This is just the beginning to some. “I’m guessing that you’ll see four to five new neobanks start up over the next 24 months,” Eric Wilson, CEO of Xinja, recently told The Sidney Morning Herald.

These neobanks are entering Australia as the country’s incumbents are facing their biggest trust challenge in decades. The Australian Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry was launched in 2017. As the name suggests, it was set up to investigate banking and financial services.

The commission was a result of several reports in the media about misconduct in the sector, including money laundering for drug syndicates.

The investigation revealed rampant toxic cultures full of misconduct, poor risk management, sales-driven commissions, giving inappropriate advice and so on.

In the end, the Royal Commission delivered a damning final report in February 2019. It revealed rampant toxic cultures full of misconduct, poor risk management, sales-driven commissions, giving inappropriate advice and so on. The Royal Commission highlighted 76 specific recommendations to the government to overhaul the banking, superannuation and financial services sector.

Since the Royal Commission ended, the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre has been inundated by companies self-disclosing breaches to anti-money laundering rules. Similarly, the country’s treasurer has told the sector’s leaders that they were “on notice” as the “public’s tolerance has been exhausted”. The chairman of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority has also urged them to step up and take more responsibility for their actions.

That being said, neobanks will still face considerable challenges. “Any firm entering against a very large incumbent has a tough time,” Richard Holden, professor of economics at University of New South Wales tells FinTech Global. “The incumbents have an obvious interesting in making life difficult for the entrants.”

And they have some advantages to make that happen. “FinTech and challenger banks have the additional hurdle of gaining consumers’ trust,” says James Butland, VP of business banking at Airwallex, the payments unicorn. “Trust is such a huge factor with a new product, especially one that handles your or your business’ money. Without a 100-year track record, trust is harder to build, but through clear communication, reliability and ensuring you are transparent, and having a product ten times better than the incumbents, trust can be built.”

Even though that trust may have been depleted to some extent following the royal commission, major banks also have the advantage of already having a large majority of customers. “[So] challenger banks face an uphill battle to grab market share,” Barry says.

Moreover, while challenger banks by definition are technically driven, the big four are by no means unfamiliar with digital banking. “For example, many of the features that Monzo, N26, Revolut or Starling offer are already offered by the major Australian banks and have been offered for years,” explains Pym.

He continues, “I think the biggest challenge for us is simply delivering something of value in the Australian market. A digital bank in Australia must be more than just an app and better than the incumbent banks apps, which are already very good.”

Even though digital banks are a reasonably new feature in the Australian financial landscape, Pym ventures a guess about how it will develop from now on. “Consumers no longer do all their banking with one bank only,” he says. “There’s a different trend now – people are choosing the best mortgage with one provider, the best deposit account with another provider, the best travel account with another provider. So if a challenger bank wants to win all of their customer’s financial life that’s going to be a really big challenge. Our objective is not to have people switch banks, so much as it is to give them an alternative to try something new and different.”

Copyright © 2019 FinTech Global